Australian banks are breaking primary support levels. There are two major reasons for this. One is the precarious level of household debt as a result of the housing bubble. The first graph below shows how housing prices have more than doubled compared to disposable incomes (after tax but before interest payments) over the past 30 years. And how household debt has risen, not as a result of, but as the underlying cause of, the housing bubble. Without rising debt there would be no bubble.

Growth in Australian housing prices is now slowing, prompting fears of a correction.

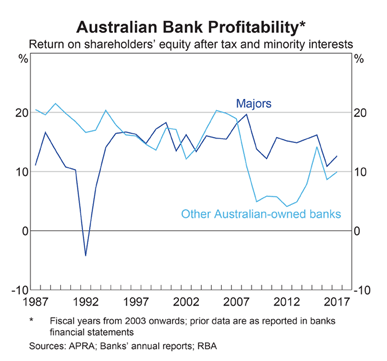

The second reason is falling returns on equity. Banking regulators have increased pressure on major banks to improve lending standards and increase capital backing for their lending exposure. For decades banks were given free rein to increase lending without commensurate increases in capital, to the extent that the majors hold only $4 to $5 of common equity for every $100 of lending exposure. Low interest rates, increases in capital and slowing credit growth have all contributed to the decline in bank equity returns to the low teens.